Reading Time: 8 min.

Publication Date: 16/05/2025

In a context that invites us to rethink cities with creativity and commitment, environmental challenges, social gaps, and infrastructure saturation present a unique opportunity to transform the way people move. Simply building more roads is no longer enough: the urban transformation of the 21st century will take place on a more human scale.

Architecture—from strategic planning to the design of public spaces—plays a key role as a catalyst for fairer, more accessible, and sustainable mobility in a world that is urbanizing at an increasingly rapid pace.

"We don't need large infrastructure projects to transform cities, but rather a new perspective on what already exists," says Carlos Moreno, the French-Colombian urbanist who created the "15-minute city" concept. This paradigm proposes reorganizing urban environments so that all essential functions (work, education, healthcare, leisure) are accessible within a radius that can be covered on foot or by bicycle in 15 minutes. Although the idea is not new, it is gaining momentum as an alternative to sprawling urban models that rely heavily on private cars.

From highways to pedestrian corridors

Cities such as Paris, Barcelona, Bogotá, and Melbourne are already applying this approach with visible results. In Paris, Mayor Anne Hidalgo's plan to eliminate 70,000 parking spaces and create "rues scolaires" (school streets free of traffic) demonstrates how architectural and urban planning decisions can shift mobility habits. In Bogotá, the Ciclovía program—which frees up 127 kilometers of streets for pedestrians and cyclists every Sunday—is a successful example of how small, recurring interventions can generate structural impacts.

According to UN-Habitat, more than 55% of the world's population currently lives in urban areas, and by 2050 this figure is expected to exceed 68%. This demands integrated, safe, and universally accessible public transportation systems.

Designing for proximity and universal accessibility

Architecture, as a project-based discipline, does not merely design buildings—it creates frameworks for living. Decisions such as designing wider sidewalks, high-quality public amenities, safe environments, and accessible routes for people with reduced mobility are deeply political, influencing who can move, how, and with what dignity.

In this regard, firms such as Gehl Architects in Denmark have developed methodologies for analyzing urban behavior, demonstrating that design directly influences active mobility (walking, cycling). Their interventions in Copenhagen have resulted in 62% of daily trips being made by bicycle.

Carlos Moreno argues that the city of the future does not need more sensors, but rather more sensitivity. This means working with existing urban fabric, regenerating it, densifying it thoughtfully, and, above all, ensuring universal accessibility as a fundamental right. "Accessibility is not just a ramp; it is the right to experience the city on equal terms," says Spanish architect and activist Izaskun Chinchilla.

Latin America: challenges and opportunities

In Latin America, the challenge is even greater. Many cities grow in a disorderly manner, characterized by urban fragmentation, dependence on informal transportation, and low levels of investment in accessibility.

In the GP Talks episode "Cities for People: from urban scale to human scale," Carolina Pereiro, Head of the Executive Project Team at Estudio Gómez Platero, points out that most Latin American cities are not designed from an inclusive perspective. During the pandemic, the significant reduction in vehicular traffic allowed for a rediscovery of public space, revealing a calmer, more accessible, and permeable city, and even enabling the reappearance of urban wildlife. However, it also highlighted significant deficits in urban infrastructure regarding accessibility and safety for certain population groups: children's mobility remains complex and risky due to the dominance of motorized transport, while older adults face similar barriers due to the lack of safe and suitable spaces for slower mobility. These reflections underscore the urgent need to rethink urban design based on criteria of inclusion, universal accessibility, and human scale.

Nevertheless, there are inspiring examples that illustrate possible pathways toward more sustainable and inclusive mobility:

Medellín, Colombia, has integrated transportation systems such as the Metrocable with proximity-based architecture and cultural facilities in historically marginalized neighborhoods. This model has successfully connected peripheral areas with the urban center, significantly improving accessibility and quality of life for residents. The combination of efficient public transportation and high-quality public spaces has made Medellín an international benchmark for social inclusion and sustainable mobility.

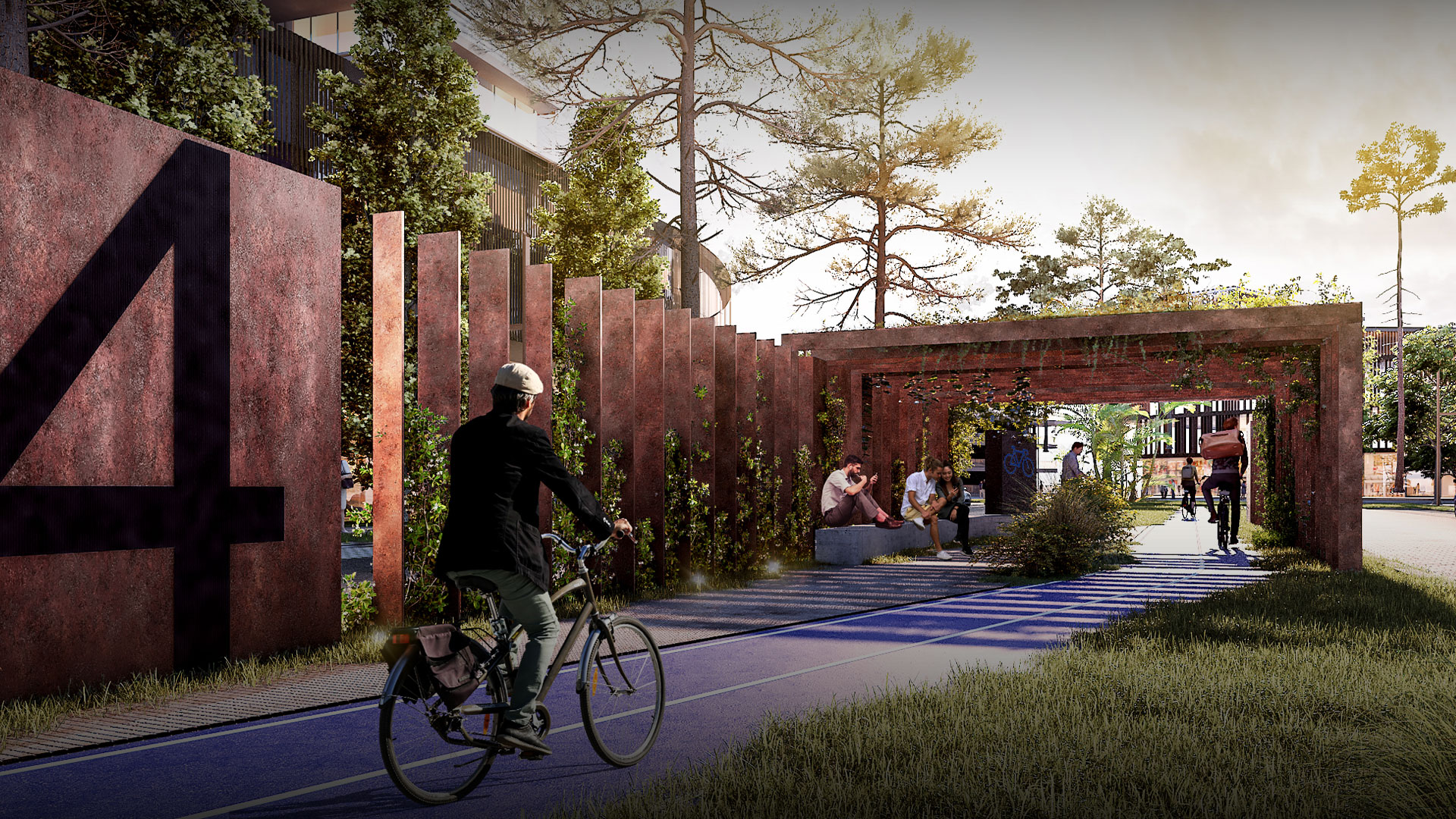

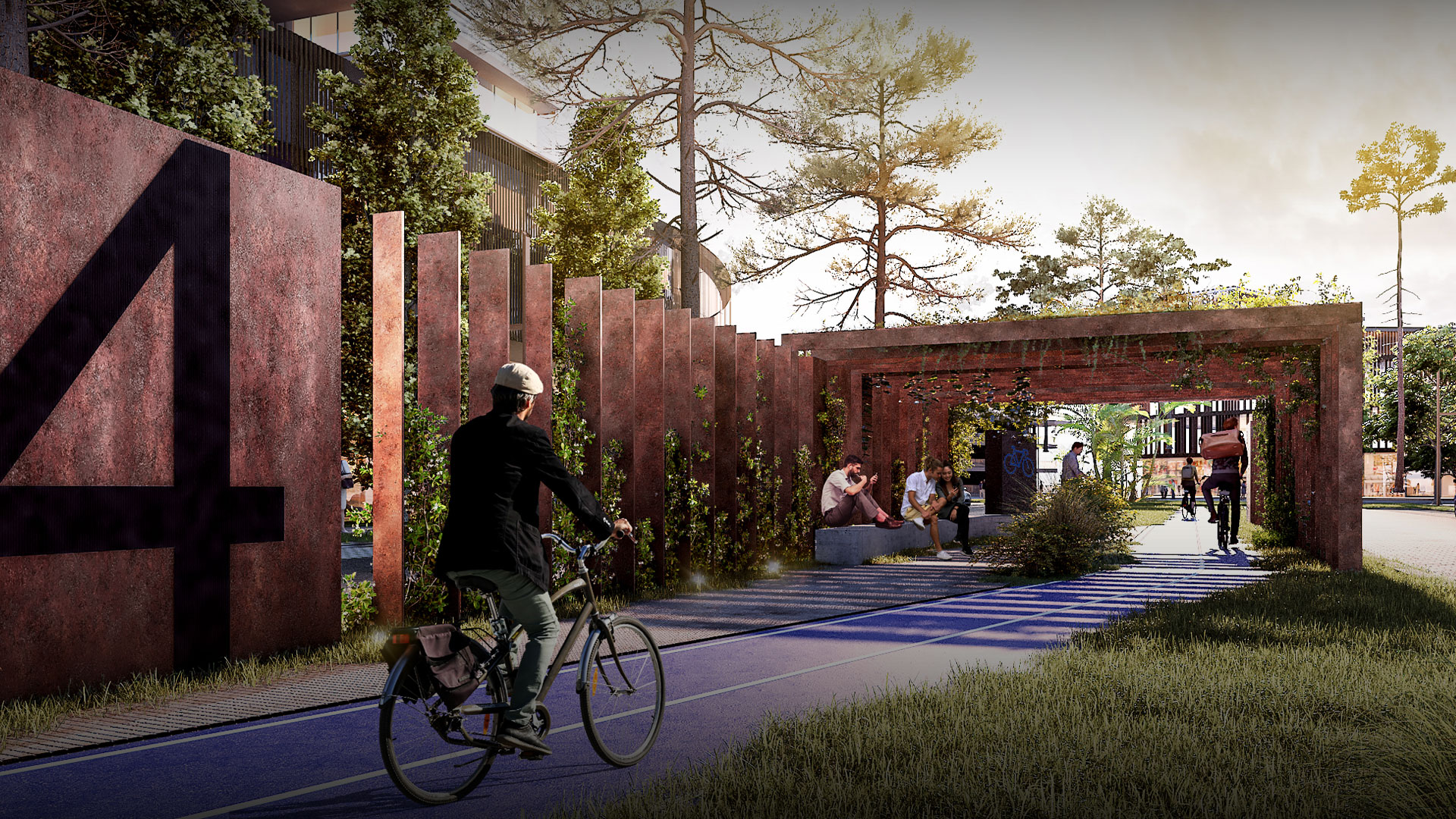

In Uruguay, the +Colonia project aims to become Latin America's first smart and sustainable city. This innovative urban development focuses on comprehensive planning that prioritizes transportation efficiency, intelligent energy management, and rational use of natural resources. +Colonia is envisioned as an urban laboratory to test new technologies and sustainable mobility solutions, such as electric vehicles, intelligent public transportation systems, and urban spaces designed specifically for pedestrians and cyclists. Its goal is to demonstrate that it is possible to create from scratch a compact, connected, and accessible city that reduces dependence on private cars and promotes healthier, more sustainable urban living.

Another relevant example in Uruguay is the renovation program for regional airport terminals, promoted by Aeropuertos Uruguay. This project recognizes the strategic importance of airport terminals as key nodes for regional connectivity and local economic development. The new terminals not only improve airport infrastructure but also seamlessly integrate air transport with other modes of ground mobility, facilitating intermodality and enhancing regional accessibility. At the same time, these architectural interventions aim to create high-quality, comfortable, and accessible public spaces that help stimulate local economies and improve the travel experience for users.

Toward integrated and human-centered urban mobility

The urban mobility of the future will not depend solely on traffic engineering, but rather on an interdisciplinary approach that brings together diverse perspectives and expertise. Within this collaborative dialogue, architecture must deepen its social sensitivity. Designing with proximity, accessibility, and everyday quality of life in mind is not merely a technical task—it is a profoundly transformative act.

Projects such as +Colonia, the renovation of airport terminals in Uruguay, and urban integration initiatives in Medellín demonstrate that it is possible to move toward smarter, more sustainable, and accessible cities. The key lies in holistic, thoughtful, and people-centered urban planning that reduces car dependency, enhances environmental quality, and guarantees universal access to the city.